If high school students took charge of their education with limited supervision, would they learn? A Massachusetts school is finding out.

“Some kids say, I hate science or I hate math, but what they are really saying is: I hate science class or I hate math class,” says high school senior Matt Whalan.

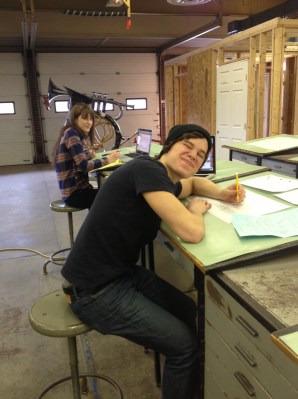

Whalan is writing a novel. That’s a notable feat for a 17-year-old, and he has a semester to finish it. Whalan is enrolled in the Monument Mountain Regional High School’s Independent Project, an alternative program described as a “school within a school,” founded and run by students. The semester-long program is in its third year, and Whalan has completed the program three times during his high school career and says it has saved his grades.

“I’ve been a writer all through high school, and my grades were suffering because I was devoted to writing instead of school,” says Whalan. Thankfully, that changed for him when a fellow schoolmate launched the Independent Project at the Great Barrington, Mass., school.

(MORE: Motivation, Not IQ, Matters Most for Learning New Math Skills)

Sam Levin, an alum of Monument who is currently a sophomore at the University of Oxford in England studying biological sciences, started the program in 2010. Frustrated with his public-high-school schedule and realizing that his friends weren’t inspired to learn, Levin complained to his mother about how unhappy he and his classmates were, to which she responded: “Why don’t you just make your own school?”

And so he did — albeit in small steps. In ninth grade, Levin started a school-wide garden that was solely cared for by students; some woke up early on Saturdays to work with the plants. The garden is still functioning and serves at-need families in the community. After witnessing the commitment that his classmates had to nurturing something they had created themselves, Levin was convinced that they were capable of putting more time and energy into their studies — as long as it was something they cared about.

“I was seeing the exact opposite in school. Kids weren’t even doing the things they needed to do to get credit. There was something at odds with students getting up to work for no credit or money [on the garden] at 7 in the morning, but not wanting to wake up to read or do a science experiment,” says Levin. “I saw the really amazing and powerful things that happened when high school students stepped it up and were excited about something.”

Levin quickly gained the support of his high school guidance counselor, Mike Powell, who remains the program adviser. After getting the O.K. from the school principal and superintendent, the duo were given the green light — amid some pushback from faculty and parents — by the high school’s Curriculum Steering Committee and the School Board to embark on their experiment in 2010.

How It Works

By its nature, since the curriculum is designed by the students, the program continues to evolve, but the core credentials remain the same. Students enroll for an entire semester, and with only a few exceptions, they do not take other classes. Each class has a mix of 10 students, some straight-A students and others who are on the verge of failing their classes. Three to four faculty advisers are available to guide the students and to provide advice, but they remain largely on the sidelines.

The semester is split in half, with the first nine weeks focused on natural and social sciences. Each Monday morning, the students formulate a question with the help of their classmates. For example, “How are plants from different parts of a mountain different from each other?” or “What causes innovation?” The students spend the rest of the week researching the answer and creating a presentation to summarize their findings to share with their classmates at the end of the week for feedback and critique. The students are in charge of keeping themselves on task, creating their research plans and meeting their deadlines.

“Teachers are the salt of the earth. They are so valuable and irreplaceable, but I just imagine them having a different role than they have had in the past for high school students,” says Levin. “Like more of a coach than a teacher at a podium.”

High school senior Ben Baum transferred this year from an alternative-learning school to take advantage of public-school offerings like Advanced Placement (AP) classes and discovered the innovative program. Before he attended Monument Mountain Regional High School, Baum had never taken biology. During his science session, he walked himself through a five-week version of an AP Biology class. With the guidance of a school biology teacher, Baum created a customized reading-and-assignment curriculum, similar to what students accomplish during a semester. “I am not a kid who doesn’t like to come to school, but it’s good to have an organization within the school that lets us do something we really care about. What we study is still really important.”

The second half of the semester covers subjects in literary and mathematical arts. For literary arts, each student picks a novel for the entire class to read each week; choices have ranged from works by Kurt Vonnegut to Oscar Wilde. In a New York Times opinion piece, Susan Engel, author of Red Flags or Red Herrings: Predicting Who Your Child Will Become, says the eight novels chosen during a semester in 2011 were more than an AP English class reads in a year.

The students similarly answer questions related to mathematics, like: “How do you develop a formula that represents the population spread of elephants?” The student who answered that question studied random mathematics and consulted a math teacher within the high school before presenting her own equation to her class.

(MORE: How Cultural Stereotypes Lure Women Away From Careers in Science)

Why It Works

“The thing I like most is that [the Independent Project] embraces learning in a way mainstream school doesn’t. It’s more about learning than being taught,” says Whalan.

By taking ownership of their learning, the students at Monument are forced to think creatively and capitalize on their own talents in order to excel. The class framework is similar to what will be expected of them in college and in the workforce, when they have to make their own educated and independent decisions.

Some faculty say the program is equally rejuvenating for teachers. “The project provides the setting for students both at risk and at the top academically to bring themselves further along. I have seen students who would never be successful in a normal schedule of the school thrive in the project,” says Lisa Baldwin, the science faculty adviser to the Independent Project. “As a teacher, I am pushed to think about diverse and challenging science topics depending on what the students are working on. I like how my work there stimulates my own love of science in a different way from my traditional classroom teaching.”

Among the defining parts of the Independent Project are the Individual and Collective Endeavors. The Individual Endeavor is a personal project each student works on throughout the semester to present to the school and their families. Individual Endeavors have included creating a film, learning to cook for 80 people, and, in Whalan’s case, writing a novel. The only requirement is the student be passionate about their chosen subject.

The Collective Endeavor is a group effort that must have a local or global impact. For one semester, students created a film about the program for other interested schools. You can watch it here:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MTmH1wS2NJY&feature=player_embedded]

“Giving young people the chance to directly engage in their own learning is rooted in a tremendous amount of research [showing] that is actually how we learn best,” says Scott Nine, the executive director of the Institute for Democratic Education in America (IDEA). “It is not surprising to me that this is a powerful experience for these students. What’s exciting is that it’s happening inside of a larger school, because it demystifies the idea that this kind of experience couldn’t be available to more young people. When we think about the world our young people live in, the core competencies of autonomy, belongingness and confidence are the building blocks of what we need in our society.”

Still, the project is not without its challenges, and the program continues to evolve. This year was the first time students in the program could receive general credit for the course instead of elective credit. Powell also says it’s not necessarily right for every student. “It is a challenge to think that a teenager can have that much freedom to figure out what they want to study and manage their time,” says Powell. “People are more on board now that they have observed the program, but there are still some skeptics with legitimate reasons, and we are always addressing challenges.”

Ezra Marcus and Brandon Curtin working on Marcus’ Individual Endeavor hydroponics project. So far, Marcus has grown lettuce sprouts inside. He’s hoping to grow tomatoes soon

Nine says the project questions many of the ways we view education, and train our teachers. “If we think about what it means to take our young people seriously like this, it raises a lot of questions about how we prepare our teachers and train them to listen and engage. How comfortable are we as a society to think about education and knowledge as less of a final answer, and more as something we are constantly learning about?”

Levin receives over 200 e-mails weekly from students, parents and school administrators with questions about how to implement a program similar to the Independent Project in their own schools. “I think that one of the beautiful things about this is that it will look different in every school,” says Levin.

His hope is that the Independent Project will continue to challenge current theories about education, and help teachers and policymakers think more creatively about the best way to help young people learn. Ultimately, that understanding should lead to systemic changes that open up more opportunities for children to get the education that will benefit them the most. “It is one thing to help school by school, and that is how a lot of change happens, but at the same time, the long-term goal and broader ambition is to make changes to the education system,” he says.