They promise a lot — from helping you to burn “fuel” to shedding pounds, but when it comes to making a difference in your health, these apps mostly fall short.

Search the Apple iTunes app store for “health” and you’ll find more than 43,000 apps that work on weight loss or fitness, such as Calorie Counter, FitBit and Nike Fuelband, or those run by Walgreens or WebMD that address more general health questions and problems. And there is a high demand for them, with an estimated 660 million downloads for apps in this category as of June 2013.

But how well are they accomplishing what they claim to do? Are they helping users to lose weight, control their blood pressure, or sleep better? In a report by the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics, researchers evaluated all of the health care apps on how well they functioned and displayed relevant health information, to whether they provided helpful and potentially motivating reminders for good health habits. The researchers also interviewed physicians and the app providers about how useful the metrics were.

Of the more than 40,000 apps, only 16,275 are directly related to patient health and treatment, meaning that they provide some type of advice and treatment guidance. The rest are spewing forth data that neither doctors nor consumers can use to improve their well being. And there is no effective way for users to evaluate the apps or rate them on how well they deliver on their promise of weight loss or ability to improve stress and mental health. “Patients currently face a dizzying array of healthcare apps to choose from, with little guidance on quality or support from their doctors. Some efforts are underway to help provide professional healthcare guidance in both the U.S. and the U.K. but these are limited in scope and impact to date,” the authors write.

(MORE: Weight Loss Apps: Don’t Waste Your Money)

For example, the researchers say, in August, Calorie Counter by MyFitnessPal, was the most popular free calorie counter and fitness tracker on Google Play, and was the second most popular app in the Apple App store. Between downloads and the app’s website, 40 million users tapped into the app’s easy way of tallying up the calories in any meal. That interest attracted $18 million in venture capital financing.

But all that attention didn’t translate into any quantifiable difference in well being. In fact, few studies have yielded enough evidence to show calorie counting from apps is effective. “It remains to be seen if there will be a “class effect” and whether one large trial with a specific calorie counting app or a fitness app will be seen as sufficient to cover all calorie counting and fitness apps,” the authors write.

One major shortcoming of the apps is that they are targeted toward smartphone users and those who are more tech savvy, which leaves out some of the populations who might have the greatest need to address chronic health issues, such as those in lower income groups and the elderly. According to the report, only 18% of people over age 65 use smart phones.

To make them more effective, the study authors identified five challenges not just for app developers but for doctors and users as well.

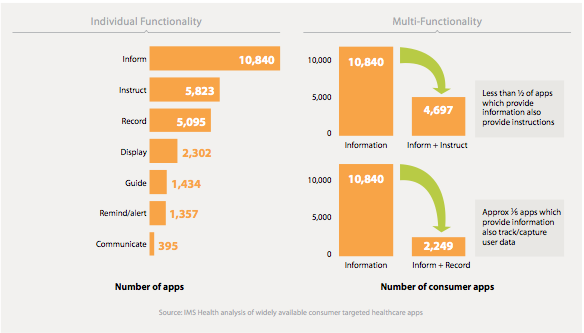

- More than 90% of the apps scored less than 40 out of 100 in functionality, which the scientists assessed using 25 screening factors such as how well the instructions guided users to getting the most out of the apps, communicating the users’ measurements, reminders about good-for-them behaviors, and the ability to record data. Many of the apps simply don’t have the capabilities they should if they are to be truly helpful. Although some include perks like blood pressure monitors, for example, others don’t even offer adequate instructions for how to use the devices.

Some only display a limited amount of information, and only 20% can incorporate data on things like exercise, diet and other factors entered by the user.

If they do flash data, they’re pretty vague about what they’re measuring. Take Nike FuelBand. What, exactly, is “fuel?” Is it the number of calories burned during a physical activity? Nike describes it as: “a single, universal way to measure all kinds of activities—from your morning workout to your big night out. Uniquely designed to measure whole-body movement no matter your age, weight or gender, NikeFuel tracks your active life.” The company says there is an algorithm that measures physical movement and turns it into an indicator of how intense that activity is, but that’s hard to translate that into a useful metric such as calories, which could help users to balance the amount they eat and amount they work off if they’re trying to watch their weight.

- Many apps provide little guidance about how the device could work for specific groups, or for specific activities. The researchers report that over 50% of the apps have been downloaded fewer than 500 times, suggesting that they are not wowing users enough to share them or convince their friends to download them as well. The researchers say this low uptake may be due to the fact that there are so many app choices that users may be confused about which app is best for their chosen sport, for instance, or their particular medical ailment.

- Most elderly, who could benefit from the monitoring that many apps provide, aren’t comfortable enough with the technology to take advantage of these devices. But the researchers say that since older populations often have younger caregivers, they may be able to benefit from apps in an indirect way with their relatives’ help.

- Most doctors currently aren’t likely to recommend health apps, both because they are unfamiliar with them and because they are not convinced that they work. If apps could improve on their efficacy, the research authors say there may be more opportunity to use them to extend the doctor’s care beyond the office, which could benefit patients. “What we hear from physicians is a lot of uncertainty about what is and is not appropriate for communicating online with patients. I think the industry could move forward by even setting up their own guidelines to getting this clarity,” said report author Murray Aitken, the executive director of IMS Institute in a press conference.

- Even if apps are effective, they won’t become a part of standard health care practice unless that efficacy is documented in solid scientific studies. “There must be recognition of the role apps can play in healthcare by payers and providers, as well as regulators and policymakers,” the authors write. App makers need to communicate that, and having strong validation for their claims in improving health is critical.

While having a gadget that tracks how high you jump or how often your pulse pushed past your target goal is entertaining, the next time you marvel at your gadget’s stats, think about how that information actually helps you. Translating that novelty information into objective health benefits will be the next challenge for health apps before they can make the claim that they are truly good for you.