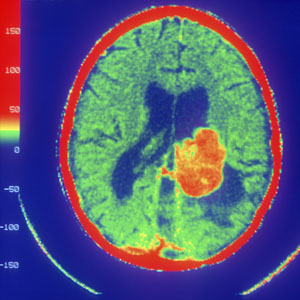

© Dan McCoy - Rainbow/Science Faction/Corbis

Glioblastoma brain tumors are notoriously difficult to fight: though they can be battled back with radiation and chemotherapy, within time they eventually manage to grow again. Yet, according to initial results of a study in mice, a technique that effectively starves the tumor of the blood supply it needs to regrow could eventually offer hope to patients diagnosed with this devastating form of cancer.

Previously, researchers from the Cancer Center at Stanford University School of Medicine found that, when tumors are targeted with radiation, the treatment also kills surrounding blood vessels feeding tumor growth. When this happens, glioblastoma tumors in particular can turn to a secondary blood supply, by producing a molecule known as hypoxic-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) that initiates a process enabling them to find bone marrow cells and use those to begin growth of new blood vessels. In this recent mouse study, however, researchers were able to cut off this “back up” blood supply by utilizing a block: a molecule known as AMD3100. (This particular molecule is already used in treating conditions such as non-Hodgkins lymphoma—given to patients prior to bone marrow transplants to ensure that bone marrow cells are confined to the blood and aren’t recruited to create new blood vessels to supply tumors with oxygen.)

In mice given a continuous infusion of AMD3100 after glioblastoma tumors were treated with radiation, HIF-1 production was blocked, preventing the return of tumors throughout the 100 day study period. In mice who had also received radiation therapy but not the AMD3100 block, the tumors returned and reached lethal proportions after an average of 70 days.

To examine the plausibility of utilizing a similar treatment in humans, the study’s authors examined the make-up of glioblastoma tumor tissue from humans who had been treated with radiation therapy. They found that, indeed, compared with tissue from tumors that had not been treated with radiation, those that had had significantly higher levels of cells derived from bone marrow. The findings were published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

This exciting development, if replicated in humans, could potentially mean a way toward preventing glioblastoma tumor—and potentially other types of tumor—regrowth after radiation. And at this point, the researchers are eager to begin human trials. Yet, in the meantime, they emphasize that routine application of the treatment—should its success be confirmed in humans—likely remains years away.