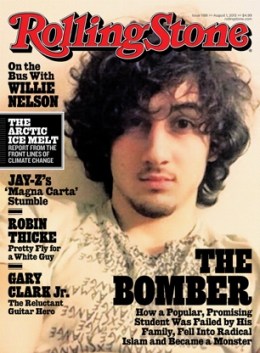

His dark eyes stare straight at the lens, his hair tousled so it falls just-so to one side, just as any teen idol or rock star would want to debut on a national magazine cover. He’s called a “monster,” but the Rolling Stone cover image of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev shows anything but such a beast. And that’s why people are so uncomfortable with it.

The cover story, “The Bomber” touts the feature as: “How a popular, promising student was failed by his family, fell into radical Islam, and became a monster.” The piece, published online on Tuesday and written by Rolling Stone contributing editor Janet Reitman, is a heavily reported look at how Tsarnaev became an infamous criminal, accused of planting explosives that killed three and injured hundreds during the 2013 Boston Marathon.

But many couldn’t make it past the cover — or vowed not to, when the issue becomes available on Friday, fueling a #BoycottRollingStone on Twitter. Two New England stores are refusing to sell the edition, and many decided not to read the magazine again. While some argue that no criminal should be glorified on a magazine cover in any form, many just can’t stomach the glamorized image of Tsarnaev, in which he resembles a “rock star.” And there’s a reason why that makes us uncomfortable.

[tweet=https://twitter.com/rosannedanielle/status/357532743816585219]

MORE: Why Some Girls Like Pretty Boys

For one, there is something called “the beauty effect,” in which we intuitively associate what is beautiful with what is good. Beauty factors heavily into how individuals assess the character of another person. Physical attractiveness, in fact, is one of the greatest predictors of who we end up liking, and beautiful people are consistently rated higher in intelligence, social desirability, happiness and success.

While seeing an attractive picture of a villainous person isn’t likely to change our opinion of that individual’s egregious acts, as the uproar over the image indicates, it could lead us to feel some emotions that we may not think are appropriate. That includes sadness, and perhaps even a douse of empathy over why an attractive person would commit a terrible crime, says Ellen Berscheid, a social psychologist at the University of Minnesota who studies interpersonal relationships.

“It is extremely difficult to separate a person’s appearance from the person’s actions, which is why it is so hard to ‘love the sinner and hate the behavior,’ says Berscheid. “Numerous studies have demonstrated that a person’s physical attractiveness level is discerned and cognitively processed within a fraction of a fraction of an instant, even when the perceiver cannot report exactly what has been perceived.”

MORE: Am I Pretty Or Ugly? Why Teen Girls Are Asking YouTube for Validation

Attraction to a bad person–even for just an instant–can cause a storm of conflicting emotions. “When there is behavioral or reputational evidence about a person that is incongruent with the person’s appearance, at least some cognitive dissonance can be expected. Such dissonance is uncomfortable and if it is uncomfortable enough it will tend to be resolved,” says Berscheid. That usually involves people re-evaluating a person’s attractiveness downward to more accurately reflect their negative behavior, or invoking excuses or mitigating circumstances to explain the individual’s actions — something akin to empathy.

That’s certainly the case here — Tsarnaev has attracted a fan base owing largely to his looks. Prior to the release of the Rolling Stone image, Slate reporter Amanda Marcotte considered why Tsarnaev has so many female supporters, who have organized themselves under ‘Free Jahar’ and emerged in force during his arraignment. “[T]hey sure do spend a lot of time sharing pictures of him on Tumblr, squealing over any behavior of his that can be construed as “cute,” and clucking maternally over his well being,” she wrote. “On Wednesday, outrage flared up in “Free Jahar” circles because of the unflattering portrayal of him in the court illustrations.”

Such allegiance is one way of resolving the dissonance people intuitively sense between an attractive criminal and his heinous acts. But for others, the conflict isn’t so easy to address, because most people appreciate the power it can have in swaying sentiment. Studies show that people tend to change their opinions when they start to identify with another person — defense attorneys rely on it routinely to portray their clients as human — as a father, mother or child of someone to whom they are important. It’s also well known in kidnapping situations; Stockholm syndrome is a coping mechanism that allows captives to relate to their captors in order to survive extended periods of forced captivity.

MORE: Why Facebook Makes You Feel Bad About Yourself

Would a mug shot of Tsarnaev have been a better option — or would that have also been considered biased, for other reasons? While editors at Rolling Stone did not respond to a request from TIME for comment on the cover, the magazine posted a statement defending the story, if not the image, with the online version of the feature:

Our hearts go out to the victims of the Boston Marathon bombing, and our thoughts are always with them and their families. The cover story we are publishing this week falls within the traditions of journalism and Rolling Stone’s long-standing commitment to serious and thoughtful coverage of the most important political and cultural issues of our day. The fact that Dzhokhar Tsarnaev is young, and in the same age group as many of our readers, makes it all the more important for us to examine the complexities of this issue and gain a more complete understanding of how a tragedy like this happens.

However people resolve the dissonance of seeing Tsarnaev looking comfortable, even attractive, on the cover of a magazine with the knowledge of what he is accused of doing, maybe the most important lesson the article, and the image, might teach us is this: that monsters might indeed look like rock stars.