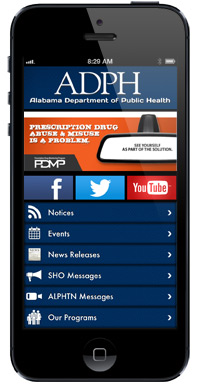

The Alabama Department of Public Health is venturing into the mobile universe as the first state with a health app for residents.

“Normally Alabama comes in last when it comes to health indicators, but we were one of the first states to be on Facebook and Twitter and YouTube. This is just another goal for us,” says Jennifer Pratt Sumner, the director of the digital media branch of the department.

The app, which is free to download from Google Play or iTunes, brings all of the social media feeds put out by the various public health divisions into one place. It also provides health news alerts and information about wellness events, such as the annual Alabama Youth Rally. Some recent tips included educational conferences open to the public, and tips on safely consuming shellfish in the state.

(MORE: Two-Faced Facebook: We Like It, but It Doesn’t Make Us Happy)

“As more and more Americans use their smartphones to gather health information, I think we’ll see a greater number of health departments rolling out their own apps,” says Alexandra Hughes, an account director at Ogilvy Public Relations Worldwide, who wrote an analysis on social media effects entitlted “Using Social Media Platforms to Amplify Public Health Messaging” [PDF]. “Consumers are already flocking to apps to do things like count calories, prepare healthier meals, and track their workouts. As a result, federal and state public health agencies have started moving beyond just a presence on Facebook or Twitter — they recognize that mobile technology is the next big thing in helping people live healthier lives,” she says in an email to TIME.

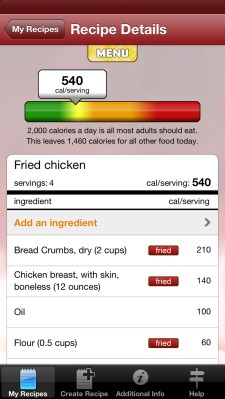

While Alabama is the first state to develop a public health app, the health department in New York City has been a pioneer in using them to reach specific populations. This month, the department released CalCutter, an app for restaurant chefs and people cooking at home. It allows users to enter in recipes and the number of servings they need to get an estimated calorie count. Users can also ask the app to convert the dish to a lower-calorie version, with ingredients that are lighter, or make it more nutritious. Originally built for independent restaurant cooks as a way to include them in the city’s effort to get more restaurants to list calorie counts, health officials saw an opportunity to help home cooks dish up healthier meals as well.

“We are doing an awful lot on obesity, and some people are trying to use the [calorie count] boards either as a way to lose weight or not gain weight. We thought, how can we make calorie counts more available in other settings?” says Dr. Thomas Farley, New York City Health Commissioner, referring to the requirement launched in 2008, that mandated all chain restaurants in the city list the calories of their offerings on their menus. “It’s very difficult for people, at least initially, to identify the number of calories in a given food item. Likewise, it’s very difficult for a restaurant that’s preparing food to know how many calories are in the items they prepare. We thought it would be nice if we made it easy for independent restaurant to calculate how many calories that are in the food they prepare so they can actually lower their calories or maybe post the calorie counts voluntarily.”

Unlike other calorie counters, CalCutter calculates calories based on varying serving sizes. Because it’s supposed to help restaurant chefs lighten up their fare, it can analyze calories in meals meant to serve over 100 people. “The overarching goal is to increase calorie knowledge and awareness, so the segment of the population that are using calorie counts can use [the app]. As part of that, the food preparers who might help those people, can use it to lower the calories in the food that they prepare,” says Farley.

The app is the fourth that the department launched over the last two years, and continues a series that Farley hopes will reach more people on a variety of different health-related issues. The others include ABCEats, which allows users to access detailed inspection reports and letter grades for the city’s 24,000 restaurants. NYC Condom informs residents where free condoms are distributed close to their current location. And Teens in NYC lets users search for city clinics that provide sexual health services for young people. All the apps were built by city department of health’s own technical staff.

“Each one of our apps has a very different audience and a very different purpose,” explains Farley. “We buy space on subways, we have ads on television. But when we have a very specialized population, we are exploring all the tools of modern information technology to reach them. So we use Facebook, Twitter and we are obviously online. But apps are another way for us to reach special groups.”

(MORE: Summer of Safe Browsing: 5 Ways to Keep Online Searching Secure for Kids)

Considering that all of the apps are fairly new, they are generating a respectable number of downloads. CalCutter, which launched on August 21 has 1,449 downloads on Android so far (numbers are not yet available for iOS). By comparison, NYC Condom and ABC Eats have a total of over 33,500 downloads each so far. New York City has a population of over 8.2 million, so the apps haven’t quite caught on, but since they cater to specific populations, city health officials are confident the outreach is working.

“Health departments need to communicate with the entire population and the populations within them. They need to use really the cutting-edge tools of today. The old mechanisms don’t go away. We will still be on television and posters on the subway. But as these new opportunities open up, we are going to continue to do them. Probably six months or a year from now people are going to be asking about entirely different uses of information technologies. We want to be moving as fast as the technology does,” says Farley.

(MORE: Why You’re More Likely to Remember a Facebook Status Than a Face)

Social media represents a major opportunity for public health campaigns, says Hughes. For one, it provides an easy way for public health workers to measure how effectively they are in getting their messages to the public, since metrics produce not just the numbers of people who receive a message, but their attitudes and responses to them as well.

“Social media metrics are more efficient than traditional process measures in their ability to gauge opinion indicators such as sentiment, and action indicators such as sharing/advocacy and self-reported behavior change, in real-time,” she writes. “Self-reporting can also be made easier through platforms such as Twitter which, for example, enable individuals to “tweet” changes in their health status or behavior.”

The same holds true for apps. And while it may be too early to tell whether Alabama or New York City’s apps actually change people’s behavior and result in healthier citizens, you can bet that public health agencies nationwide will be watching closely to see if they do.