Rural areas have historically had higher suicide rates than urban areas, and most experts believe it’s a combination of several things: higher gun ownership per capita, more isolation from friends, family and suicide prevention resources, and a by-the-boot-straps culture. In the suicide prevention field, Wyoming is a perfect storm.

To start, the state is fourth in gun ownership rates. Keeping guns out of the hands of those with mental illness became a topic in gun control debates across the country after the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., largely focused around the problem of homicide. But gun suicide is actually a bigger problem than gun homicide. According to a report by the Institute of Medicine and the National Research Council, gun suicide accounted for 61 percent of the 335,600 people who died from firearm-related violence between 2000 and 2010.

Besides Alaska, Wyoming also has the lowest population density in the U.S. and only one call center networked to the national lifeline. To counteract the state’s macho culture of self-sufficiency, which often prevents men from seeking help, Wyoming’s mental health officials decided to go looking for them. Last year, the Wyoming Department of Health began reaching out to men who had attempted suicide to better understand why they did what they did and found 10 middle-aged men willing to speak candidly one-on-one.

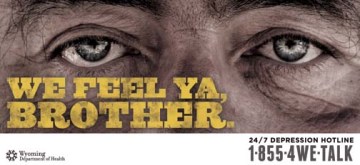

One of several posters created by the Wyoming Department of Health aimed at middle-aged men at risk of suicide. Wyoming has more suicides per capita than any U.S. state.

“When we sat with them, we said, ‘Tell us your story, and go way back,’” says Rich Lindsey, a technical consultant hired to work on Wyoming’s suicide prevention campaign. “We discovered that if you’re going to effectively get to them, you need to go upstream in their life, at a point where things are going wrong but they’re not yet thinking about suicide.”

Lindsey discovered that trying to target a campaign to someone who was already thinking about suicide was more likely to fail because that person was already shutting themselves off from the world around them. The chances of reaching them at that point were slim.

So the state took that information and developed an awareness campaign consisting of local TV ads, billboards and posters featuring an older, rugged man with bushy eyebrows, lonely eyes and phrases like “We feel ya, brother,” “It’s tough out here,” and “Get out of hell,” as well as a unique phone number so they could track the response rate.

The one-county, $50,000 pilot program elicited 10 calls from February to June. Lindsey says it’s too early to says the campaign is a “win,” but it’s been effective enough that the program will be expanded to two more counties. For those who advocate upstream approaches, the Wyoming experiment may be viewed as a model. But for others, $50,000 on a public awareness campaign and a mere handful of calls may not seem worth it.

LifeNet, 11:25 a.m.

Santiago is logging in her previous caller, the man who had called six times that morning. She says he wasn’t actively suicidal and told her that talking to the call center’s crisis counselors helped him make it through the day. But she thought if he called back a seventh time, she would explore getting him to an emergency room.

“What are the chances he’s calling back?” I ask.

“Oh, he’s calling back,” Santiago says. By the end of the day, Santiago will have answered 20 to 25 calls from any one of the 14 different hotlines.

You may think that a suicide prevention office would be a dreadful place to work, but it’s really just like any other around the country: idle chatter near the water cooler, lunch breaks with co-workers, cinnamon rolls in the break room. It’s just that from this room, lives are being profoundly affected every day. And even though the exact number of people who have truly been helped will never be known, the lifeline has very strong advocates, including Kevin Hines.

Hines’ story is not merely dramatic; it’s a test case in how the mental health system broke down. There are essentially three main ways to prevent suicide: treatment; means prevention; and access to prevention resources. At the time, Hines wasn’t properly being treated for bipolar disorder; the Golden Gate Bridge has no physical barriers to prevent suicide attempts; and as for the bridge’s suicide prevention call box, Hines didn’t know it was there.

“Had I known, I’m sure I would’ve called,” he says, “because I desperately wanted to talk to somebody.”

Back in New York City’s suicide prevention call center, I ask Draper if it’s difficult to come in to work each day, to motivate his employees to take another call and assure them that what they’re all doing is actually working.

“When I tell people what I do, they say, ‘Oh, Draper, that must be really depressing,’” he says. “And I say, man, I’m in the suicide prevention business, not the suicide business. What I see every day and what our crisis center staff hears every day is hope. And they know that they’re a part of that.”

He says it’s important to remember that 1.1 million adults are attempting suicide every year, but 38,000 are actually dying by suicide.

“What that is telling us is that by and large, the overwhelming majority of suicides are being prevented,” he says. “And those stories are not being told.”

SEE ALSO: The Big Surprise of Martin Luther King’s Speech

Correction: A previous version of this story stated that in fiscal year 2014 SAMHSA requested $8 million less for suicide prevention measures than in 2013. The department requested $8 million less compared to fiscal year 2012.