Prostate cancer cell

The data on PSA testing to detect prostate cancer has long been shaky — so much so that the discoverer of PSA (or prostate-specific antigen, an enzyme made by the prostate) himself decried the test two years ago as “hardly more effective than a coin toss.”

He characterized the widespread use of the cancer-screening tool as “a hugely expensive public health disaster.” This week, the U.S. National Preventive Services Task Force concurred, officially recommending against PSA screening for all healthy men of any age.

So why do people — particularly cancer patients and their advocates — continue to support the routine use of ineffective tests? In the case of PSA tests, positive results often lead to unnecessary and painful biopsies and the treatment of tumors that would never have harmed the patient anyway, further leading to side effects like infection, incontinence, impotence, even death.

(MORE: Prostate Cancer Screening: What You Need to Know)

Similarly, why do women resist recommendations to scale back routine breast cancer screening with mammography, when doing so would reduce their risk of unnecessary and painful interventions and treatments?

A new review explores some of the psychological reasons for the resistance, and offers a possible solution. The first reason, say researchers Hal Arkes of Ohio State University and Wolfgang Gaissmaier of the Max Planck Institute in Germany, is one that every journalist and medical quack knows well: a good anecdote often trumps even the most overwhelming statistics.

Prostate and breast cancer survivors and their families certainly have compelling stories, which are frequently given intense media attention, particularly when famous people, such as Rudy Guiliani or Warren Buffett, are affected.

(MORE: Warren Buffett’s Prostate Cancer: “I Feel Great”)

But survivor stories don’t have to involve celebrities to make an impact. “Most people know someone — their mailman’s older brother — who had a positive PSA test and he’s still alive after treatment. So that shows the PSA test saved his life,” explains Arkes.

Research shows repeatedly that while a single story of an individual case will compel people to take action, cold statistics on hundreds of cases may make action less likely. This means that government task force guidelines — such as those on prostate cancer and breast cancer screening — based on data on thousands of cases may play less of a role in people’s medical decision-making than their knowledge of one case of someone they know. This is true whether the case represents a rare outcome or a common one.

“If you have a person standing in front of you who says, ‘I had my life saved by a PSA test,’ that’s powerful. It makes a big impression and hits you right on the retina, whereas if you see some statistic saying this many men had positive PSA tests and false-positive this and that, your eyes glaze over,” says Arkes.

(MORE: When Cancer Screening Does More Harm than Good)

Another reason people adhere to personal experience is that they have a deep-seated need for suffering to be meaningful. So, the more you have suffered or paid for an experience, the more valuable it becomes. The phenomenon applies to minor costs — research finds that people who paid more for the same dinner describe it as more enjoyable — as well as major ones. If you have endured surgery, chemo or radiation, and particularly if you have suffered terrible side effects as a result, you are more likely to believe that — despite what the statistics say — you were one of the lucky ones for whom treatment was lifesaving. You’ re not likely to believe that your pain was unnecessary.

This need for meaning is completely understandable and human, but it, too, can skew decision-making, especially when these stories feature prominently in a debate. Fortunately, there may be a relatively simple way to get around these quirks of human nature and help people make informed choices about complex issues including cancer screening.

(HEALTH SPECIAL: Cancer — The Screening Dilemma)

The authors of the new study cite previous research that asked people to make hypothetical choices for the treatment of heart disease. The participants were given information showing that one option had a 75% cure rate, while another had a 50% cure rate. They were also told anecdotes about other patients that either represented the data accurately or made it seem like the success rates of both options were equal. People who heard the misleading anecdotes were twice as likely to choose the less successful treatment option.

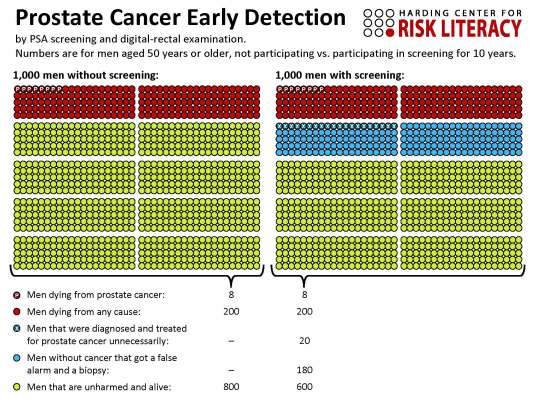

However, when participants were presented with a graphic representation of the cure rates — similar to the graphic, below, on outcomes of prostate cancer screening — they were not as swayed by misleading anecdotes. People tended to choose the more successful treatment option.

Other studies have also suggested that data visualization helps people better understand information, which has led to the development of drug fact boxes based on this principle.

Of course, most people remain terrified of cancer no matter what the data say, and so they may seek screening because it offers some sense of control. Using visual data that “hits the retina” like an anecdote could help people make critical choices that are actually better for their health.

The research was published in Psychological Science.

MORE: Q&A: Two Harvard Docs Talk About Making the Best Medical Choices

Maia Szalavitz is a health writer for TIME.com. Find her on Twitter at @maiasz. You can also continue the discussion on TIME Healthland‘s Facebook page and on Twitter at @TIMEHealthland.