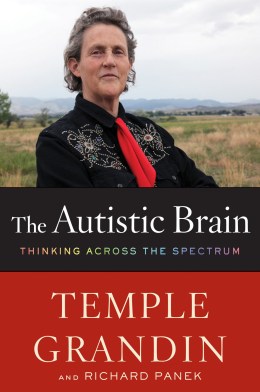

Temple Grandin authored the memoir The Autistic Brain with Richard Panek ( order now)

Temple Grandin, a professor of animal science at Colorado State University, eloquently described life from the perspective of someone living with autism in her memoir, Thinking in Pictures, which served as the basis for an Emmy-winning HBO movie. With her latest book, The Autistic Brain, Grandin uses her own experience to take readers from the first diagnoses of the developmental disorder to the latest research involving neurological imaging and genetics that are helping to reveal more about the condition. In the following excerpt, Grandin addresses the importance of identifying and encouraging the strengths and talents of people on the autism spectrum to highlight the measurable ways they can contribute and participate in society.

(MORE: Q&A: Temple Grandin and The Autistic Brain)

I don’t know how my own brain might have changed over the years, but I do know that as my career has shifted, so have my abilities. I haven’t been doing drawings for more than 10 years now, partly because of changes in the industry. The fax machine was the ruination of good architectural drawings. Clients would say to me, “Oh, just shove it in the fax,” and then they’d use the fax as their blueprint. I lost the motivation to make a really nice drawing. But at the same time, my professional priorities were changing. I was becoming a lot busier giving lectures, and many people have told me that my speaking style became more and more natural. That was hard work. I knew I had to train myself to be someone I wasn’t naturally, and what is training yourself at a new skill but “rewiring” your brain?

This generation is fortunate in an important way. They’re the tablet generation — the touchscreen, create-anything generation. I’ve already talked about how these devices are an improvement over previous computers because the keyboard is right on the screen; autistic viewers don’t have to move their eyes to see the result of their typing. But tablets also have other advantages for the autistic population.

First, they’re cool. A tablet is not something that labels you as handicapped to the rest of the world. Tablets are things that normal people carry around.

Second, they’re relatively inexpensive. They’re even less expensive than high-end personal communication devices traditionally used in autism classrooms.

And the number of apps seems limitless. Instead of a device that performs a few functions, a tablet taps into a world of educational opportunities. You have to be careful, of course. I saw an educational app that visually was quite cute — it featured Dr. Seuss characters — but its approach was inconsistent. If you touched the image of a ball, the tablet said, “ball.” But if you touched the bicycle, it said, “play,” and if you touched the wall, it said, “house.” Those words are too abstract. It needs to say, “bicycle,” and it needs to say, “wall.” But the better programs and apps say what they mean, and they can be invaluable in helping nonverbals communicate.

These days you can get a whole education online. Numerous websites and high-tech tools that offer amazing opportunities have cropped up. The names and aims of these sites will undoubtedly change over the years, but at the moment here are some of my favorite educational accessories that are perfect for some autistic brains.

• Free videos. Khan Academy offers hundreds if not thousands of educational videos and interactive graphics in dozens of categories. You’re a pattern thinker who wants to know more about computer programming? Try the code-writing-for-animation category. You’re a picture thinker? Browse the hundreds of art-history videos that cover historical movements, geographical specialties, and individual artists and artworks.

• Semester-long courses. Coursera offers free courses from more than 30 universities. And the courses are changing all the time. Your kid is a science geek who’s interested in the universe? You’re in luck. A professor from Duke University is teaching a nine-week Introduction to Astronomy course, three hours of video instruction per week. You’re a word-fact thinker who wants to write poetry? Learn from the masters with Modern and Contemporary American Poetry, a 10-week course taught by a University of Pennsylvania instructor. Udacity is another gateway to free courses, though ones with a more mathematical emphasis.

• Check out the universities themselves. I just typed Stanford and free courses into my browser, and up came a list of 16 courses for the fall semester, including Cryptography and A Crash Course on Creativity. In 2012, Harvard, MIT, and the University of California at Berkeley created a nonprofit partnership in free courses called edX.

• 3-D drawing tools. They’re free, they’re downloadable and they range in complexity. My personal favorite is probably SketchUp.

• Desktop 3-D printers. The programs — like SketchUp — are free, and the printers are dropping in price. Yes, they’re expensive at the very moment I’m writing this sentence — about $2,500 for a low-end but perfectly serviceable model. But at the rate technology changes, that price has probably dropped to $2,400 in the time it took me to write this sentence.

I’m certainly not saying we should lose sight of the need to work on deficits. But as we’ve seen, the focus on deficits is so intense and so automatic that people lose sight of the strengths. Just yesterday I spoke to the director of a school for autistic children, and she mentioned that the school tries to match a student’s strengths with internship or employment opportunities in the neighborhood. But when I asked her how they identified the strengths, she immediately started talking about how they helped students overcome social deficits. If even the experts can’t stop thinking about what’s wrong instead of what could be better, how can anyone expect the families who are dealing with autism on a daily basis to think any differently?

I’m concerned when 10-year-olds introduce themselves to me and all they want to talk about is “my Asperger’s” or “my autism.” I’d rather hear about “my science project” or “my history book” or “what I want to be when I grow up.” I want to hear about their interests, their strengths, their hopes. I want them to have the same advantages and opportunities in education and the marketplace that I did.

I find the same inability to think about children’s strengths in their parents. I’ll say, “What does your kid like? What is your kid good at?” and I can see the confusion in their faces. Like? Good at? My Timmy? I have a routine I follow in these cases. What’s your child’s favorite subject? Does he have any hobbies? Does she have anything she’s done — artwork, crafts, anything — that she can show me? Sometimes it takes a while before parents realize that their kid actually has a talent or an interest. Two parents came up to me recently and said they were concerned because they knew their son wouldn’t be able to handle the family business, a ranch. What would become of him, since that was the only world he’d ever known? Well, yes, it might be the only world he’d ever known, but the kid wasn’t nonverbal. Their kid could function. So what part of that world interested him? Fifteen minutes later, they finally said that their son liked fishing.

“So maybe he can be a fishing guide,” I said.

I could almost see the lightbulbs popping to life above their heads. They now had a way to rethink the problem. Instead of thinking only about accommodating their son’s deficits, they could think about his interests, his abilities, his strengths.

For me, autism is secondary. My primary identity is as an expert on livestock — a professor, a scientist, a consultant. To keep that part of my identity intact, I regularly block out chunks of the calendar for “cattle time.” The month of June? That’s cattle time. The first part of January? That’s cattle time. I don’t take speaking engagements during those periods. Autism is certainly part of who I am, but I won’t allow it to define me.

The same is true of all the undiagnosed Asperger’s cases in Silicon Valley. Being on the spectrum isn’t what defines them. Their jobs define them. (That’s why I call them Happy Aspies.)

Some people, of course, will never have that opportunity. Their difficulties are too severe for them to cope without constant care, no matter how hard we try.

But what about those who can cope? And what about those who can’t cope but who can lead more productive lives if we can identify and cultivate their strengths? How can we turn the plasticity of the brain to our advantage?

O.K., let’s take it one step at a time. First things first: How do we identify strengths?

One way is to apply the three-ways-of-thinking model that I discussed earlier: picture thinker, pattern thinker, word-fact thinker. That model, I believe, can help fundamentally change education and employment opportunities for persons with autism.

(MORE: New Study Suggests Autism Can Be ‘Outgrown’)

Excerpted from The Autistic Brain: Thinking Across the Spectrum. Copyright © 2013 by Temple Grandin and Richard Panek. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.