The first cases emerged at the end of June, and health officials have only just identified the possible source of the cyclospora contamination that has sickened more than 400 people. Why is the outbreak so difficult to track?

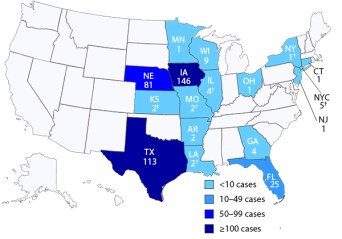

Iowa health officials first reported two cases of stomach illness that state labs traced to the cyclospora parasite to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on June 28. Since then, health departments in Texas, Nebraska, Florida, Wisconsin, Georgia, Illinois, Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Connecticut, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio have all reported cases of the infection, which are generally caused by contaminated water or food. Cyclospora is more common in tropical countries, and in the past, outbreaks in the U.S. have been caused by produce imported from these regions.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) says that in two states — Iowa and Nebraska — the source of the parasite was a salad mix produced by a Mexican farm and sold to Olive Garden and Red Lobster restaurants. Taylor Farms de Mexico, a subsidiary of Taylor Farms of Salinas, Cal., is cooperating with the agency’s investigation, and officials are evaluating the farm’s processing facility to determine how the parasite entered the food supply.

(MORE: What We Know (and Don’t Know) About the Latest Stomach Bug Outbreak)

That still leaves people who were sickened in 14 other states wondering what made them ill, and a public with unanswered questions about how they can protect themselves from becoming part of the case count. The FDA has still not confirmed whether the salad mix was also sold in grocery stores, and the agency is trying to determine if all of the cases in the country are connected to the same contaminated salads from Taylor.

Both Olive Garden and Red Lobster are owned by the Orlando-based Darden Restaurants. Darden spokesman Mike Bernstein said the announcement was “new information. Nothing we have seen prior to this announcement gave us any reason to be concerned about the products we’ve received from this supplier,” he said in a statement to the Associated Press. The Orlando Sentinel reports that Suzanne Matteis of Dallas is suing the company since she was sickened by cyclospora after eating at an Olive Garden.

In a news statement on the Taylor Farms website, the company says the FDA audited the plant in 2011 and found “no notable issues.” In addition, the company says, “In this past month of June, Taylor Farms de Mexico produced and distributed about 48 million servings of salads to thousands of restaurants in the Midwest and eastern United States. Our team is dedicated to ensuring each of the two million salads we produce every day at Taylor Farms de Mexico is healthy and wholesome.”

Cyclospora is a tiny, one-celled parasite that can cause weeks and sometimes even months of very uncomfortable stomach problems including diarrhea and explosive bowel movements as well as loss of appetite, cramps, nausea and fatigue. Most of the cases resolve on their own, but severe symptoms can be treated with antibiotics. Some cases are especially challenging, since symptoms can subside, only to reappear several more times.

(MORE: Bad Food: Illnesses from Imported Food are on the Rise, CDC Says)

But what took so long to identify the source of the infections? And why are salads from Mexico only linked to cases in two states? Identifying the correct brand, distribution channel and lot numbers of a suspected source of foodborne illness is critical, says the FDA, and the agency only releases information after it has gathered enough epidemiologic, laboratory and environmental information to implicate a specific food. “Obtaining a complete and accurate understanding of the entire chain of distribution from manufacturing to retail is a challenge in outbreaks,” says Theresa Eisenman, an FDA spokesperson to TIME in an email. “In some situations, there can be hundreds of entities including wholesalers, brokers, distributors and retailers. In many cases, the records are not in electronic form and require extensive, time-consuming, manual data collection and review.”

One factor slowing down the process is the fact that cyclospora is relatively uncommon in the U.S., so confirming the presence of the parasite takes time. “It is a rare parasite in the U.S. So it is not commonly tested for, and it’s a specific test,” says CDC spokesperson Leslie Dorigo. Upset stomachs and feeling quesy can be caused by a number of different things, and people coming to the hospital with these symptoms may not be immediately tested for cyclospora, which makes it difficult for investigators to get a handle on how many people were affected and to determine if all were sickened by the same bug. “People come in with the common stomach bug symptoms, but it takes a bit longer to get diagnosed because it’s a slow onset. The time between infection and getting sick is about a week, so it is hard to determine what caused it and when,” says Dorigo.

But food safety advocates argue that moving quickly is important to address public fear and minimize the damage that these products can have on people’s health as well as on an industry’s bottom line. While the tainted bagged salads in the current outbreak are probably no longer on the market, for example, fear of getting sick may drive consumers away from bagged salads in general.

(MORE: Food Safety: CDC Report Shows Rates of Foodborne Illnesses Remain Largely Unchanged)

For now, for anyone who was sickened outside of Iowa or Nebraska, both the FDA and the CDC recommend cleaning produce by thoroughly washing any fresh products before eating them and washing hands, utensils, and surfaces with hot, soapy water before and after preparing food. You can stay informed of the investigation on the CDC site, here.