Kevin Hines paced along the Golden Gate Bridge, trying to figure out whether to obey the voices in his head urging him to jump. Anyone paying the slightest attention to Hines should’ve seen that something was horribly wrong. Sure enough, after about a half-hour, a woman approached him. Hines thought she was there to save his life.

Instead, she was a tourist wanting Hines to take her picture. The look of desperation on his face apparently didn’t register. Elation crumpled into despair. “Nobody cares,” he thought. “Absolutely nobody cares.”

Hines soon hurdled a railing, stepped out onto a ledge 25 stories above San Francisco Bay and jumped. He immediately regretted it. Falling 75 miles an hour headfirst toward the water, Hines realized that if he was going to save himself, he had to hit feet first. So he threw his head back right before he plunged 80 feet into the cold waters, shattering two of his lower vertebrae. He eventually surfaced and was rescued by the Coast Guard. Only one out of 50 who jump survive.

Thirteen years removed from his attempt, Hines is now an author and lecturer, and doing quite well considering his experience. Hines frequently travels around the country talking about what happened on September 25, 2000. Diagnosed with bipolar disorder, he still has auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid delusions. But today, he has a support network of family and friends that check up on him and identify early warning signs that could lead to Hines harming himself again. He logs his symptoms into an online document he shares with others so they can keep an eye on him. Hines says that’s what separates him from so many others who have suicidal thoughts.

“When you learn to be self-aware with mental illness, you can save your own life,” Hines says.

In May, the Centers for Disease Control released data showing that in 2010, 38,364 people weren’t able to save themselves. For the first time, the number of suicides surpassed deaths from motor vehicle accidents and most researchers believe that number is low, if anything, because many suicides go unreported. The suicide rate for Americans aged 35 to 64 rose 28.4 percent from 1999 to 2010. According to the CDC, $35 billion is lost due to medical bills and work loss costs related to suicide each year. And while suicide rates are not as high as they were in the early 1990s, they’ve climbed steadily upward since 2005.

As more Americans commit suicide, some in the field question the effectiveness of current prevention programs. Over the last 15 years, public policy and federal funding have shifted toward a broader mental wellness movement aimed at helping people deal with anxiety and depression that could eventually lead to suicidality. But that shift may have left those most at-risk of suicide, like Hines, without the support they need.

One program sits at the intersection of those two approaches. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, which expects 1.1 million to 1.2 million calls this year and receives about 15 percent more callers each year, is broadly marketed to the general public through billboards and ads that reach those suffering from anxiety, depression and loneliness but are often not actively suicidal. At the same time, it’s an emergency resource for those who are at immediate risk of killing themselves and who struggle with chronic mental illness. But some in the field question its effectiveness, along with the effectiveness of many other services and programs funded and promoted on a national scale. Those in the field often use the metaphor of a river to illustrate the divide: Is it worth getting to more people upstream or narrowly targeting those like Hines downstream?

At the Waterfall

The bridge phone inside New York City’s suicide prevention call center only rings about once a month. But when it does, often in the middle of the night, it emits distinct, deep chirps – as if the phone itself is in distress. The operators manning the 24/7 LifeNet hotline recognize the ring immediately. It means someone’s calling from one of the area’s 11 bridges, and they’re likely thinking about jumping.

LifeNet, a mental health and suicide prevention hotline servicing New York’s metropolitan area, is located in the H2H Connect Crisis Contact Center, which serves as one of 161 call centers that make up the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline network, headquartered in the same building. During its busiest hours from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m., the hotline has roughly 20 operators working the phones inside their unassuming L-shaped office space in lower Manhattan. The operators could easily be mistaken for a collection of telemarketers. The large computer screen at the head of the call center showing the number of lines being processed could easily reside inside QVC’s customer service center.

(MORE: Childhood Vaccination Rates Good, But Measles Cases Hit Record High)

You don’t get a sense of what truly happens in this room until you run across the bridge phone, which is a direct line to the call center. It’s LifeNet’s equivalent of the Oval Office’s mythical red phone. On the wall above it, black Ikea picture frames display detailed information for each bridge and the locations of its call boxes: “Northbound 3rd Avenue Exit,” “Westbound Light Pole 60.” If someone calls, they can use the caller ID, check the information above the phone and immediately locate the caller and send help.

If it were up to those who work at LifeNet, however, they would get rid of the bridge phone altogether. “What we want is to get people upstream,” says John Draper, director of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. “We don’t necessarily want to get people who are on the edge of the waterfall. If they are, we can help them. But it’s a huge cost savings for the entire mental health system if you can get people further upstream.”

Draper is the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline’s soft-spoken, goateed, pony-tailed director and a whole-hearted advocate for early treatment. Talk to him and you realize why he’s in this field, something, he says, chose him. Draper speaks calmly but with purpose. He looks you in the eye. He routinely uses your name in conversation.

In the 1980s, Draper was part of a mobile crisis team, a group of clinicians that goes into the homes of people who are psychiatrically ill but unable or unwilling to get help. He says he soon came to the realization that the country’s mental health system operated behind bricks and mortar, “where it waits for people.”

“It says, ‘Ok, you’re mentally ill?’ I’ll see you Tuesday at 9 a.m. Hope you can make it.’ The system is not set up for the convenience of the user,” he says. “And as a result, two-thirds of the people with mental health problems in this country never seek care. So here was this program that goes into people’s homes. I was like, man, this is the way it should be.”

A decade later, the Mental Health Association of New York City established a 24/7 crisis information and referral network and hired Draper. Several years later, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and now funds the national lifeline with $3.7 million annually, assessed callers who had contacted crisis centers like New York’s and found that most of them felt less distressed emotionally and were less suicidal after the call. Draper calls it a groundbreaking finding.

LifeNet came into its own in 2001 when it became a central resource for those affected by the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, which in New York City was just about everybody. People were reporting depression, anxiety and other traumatic responses in massive numbers. LifeNet’s call volume and staff doubled, and it’s never gone down. That time in the spotlight positioned the hotline to administer the national suicide prevention lifeline starting in 2004.

Today, Draper and his staff oversee a network of more than 160 independently operating call centers around the country. Call 1-800-273-TALK, and you’ll be routed to the call center closest to the phone number from which you’re calling. The staff helps develop risk assessment standards for operators around the country so they can consistently and quickly determine the seriousness of a situation over the phone.

Draper expects call volume to increase again this year. About 8 million adults in the U.S. are thinking seriously about suicide, but only 1.1 million actually attempt it. So when Draper sees the volume actually reaching that 1.1 million number, which he expects it to this year, he views it as a good thing.

“If your calls are increasing, does that mean more people are in distress?” he says. “That’s not necessarily true. It means more people may have been in distress all along but didn’t know this resource was there. So the more we promote awareness of this resource, once it gets out, then it stays out there.”

The problem for people like Draper is definitively determining whether suicide prevention efforts are working. The only way you ever know if you’re saving someone’s life is if they come out and say so, and that makes it difficult to truly gauge the effectiveness of the lifeline or any other prevention program or service.

“The lifeline is a valuable addition to our efforts,” says Dr. Lanny Berman, executive director of the American Association of Suicidology (AAS). “It’s indeed a resource for people in suicidal crisis to reach out immediately and get help. Whether it is effective in saving lives remains to be seen.”

But some of the available data seems to indicate that the lifeline is having a positive effect. Studies done by Columbia University’s Dr. Madelyn Gould have found that about 12 percent of suicidal callers reported in a follow-up interview that talking to someone at the lifeline prevented them from harming or killing themselves. Almost half followed through with a counselor’s referral to seek emergency services or contacted mental health services, and about 80 percent of suicidal callers say in follow-up interviews that the lifeline has had something to do with keeping them alive.

“I don’t know if we’ll ever have solid evidence for what saves lives other than people saying they saved my life,” says Draper. “It may be that the suicide rate could be higher if crisis lines weren’t in effect. I don’t know. All I can say is that what we’re hearing from callers is that this is having a real life-saving impact.”

LifeNet, downtown Manhattan, 10:15 a.m., Wednesday, June 5

Dely Santiago puts on her black Sennheiser headset and takes a look at the queue. Five callers waiting to speak with an operator. A dozen others on the line.

Like its hometown, New York City’s suicide prevention call center never sleeps, and Santiago is one of 50 employees that keeps it running day and night. Santiago, 29, has been working in the mental health field since she was 18, as a behavior modification specialist and a psychotherapist. She began working for LifeNet in 2009 as a crisis counselor and is now an operations manager, primarily tasked to supervise operators – but she still takes calls.

Santiago uses just one phone, but 14 separate hotlines feed into it. There’s the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, of course, and LifeNet, New York City’s local mental health and substance abuse line. But there’s also Spanish LifeNet; Asian LifeNet; Project Hope (for victims of Hurricane Sandy); BRAVE (an anti-bullying line); a Disaster Distress Helpline; an NFL Lifeline (for those with football-related mental health issues). Many of the operators are trained to answer all of them.

This morning, Santiago’s first call is from OASAS Hopeline, the New York state hotline for substance abuse. While she never knows exactly who’s calling, she always knows which line is coming through. If a LifeNet call pops up on her caller ID, it’s often someone reaching out for basic information about clinics or resources in the area. That’s low stress. But if it’s the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, she takes deep breaths before answering so she can stay calm. This one, the state’s addiction line, is somewhere in the middle.

On the line, Santiago runs through a series of questions to get a sense of the seriousness of the call. Her voice is soothing, lilting even, but firm.

“You obtained a DWI in which county?”

“Has alcohol been an ongoing issue for you?”

“Any thoughts of suicide or hurting anybody else?”

The operators routinely ask callers whether they have suicidal thoughts, even on non-suicide prevention calls, because there’s no way to tell whether a substance abuse call could quickly turn into a suicide call. You just have to ask. That way, you increase your chances of helping them upstream.

The queue doesn’t let up. Several people are on hold. More are talking to operators. Once a crisis counselor has finished a call, each one is logged in to a database with a report number and a brief description. They get three minutes to log it in and take a breath before the phone rings again.

“Hello, LifeNet,” Santiago says. “How may I help you?”

Casting a Wide Net

Many programs that receive federal funding, like the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, are widely advertised nationwide, something DJ Jaffe thinks should be targeted instead to those most at risk.

Jaffe is the founder of Mental Illness Policy Org and got involved after his sister was diagnosed with schizophrenia in the mid-1980s. “A lot of suicide prevention campaigns are based on reaching out for help if you’re feeling depressed rather than calling if you’re truly suicidal,” he says. “That’s being funded with suicide dollars. Telling someone who’s feeling bad to reach out. Is that going to reduce suicide? Spending massive amounts of money marketing to the public via television shows, PSAs, billboards? It’s a giant waste of money because we know where we can focus it.”

AAS’s Berman is similarly critical of public awareness campaigns promoting services like the lifeline. “The general zeitgeist in the field is public education is good, and it’s better that people know about the problem and really know that prevention is possible,” he says. “But I don’t know that public awareness campaigns work for the people you most want to reach, the people who are already suicidal.”

(MORE: First Lady: Americans Need to Drink More Water)

A 2009 study in the journal Psychiatric Services looked at 200 publications between 1987 and 2007 describing depression and suicide awareness programs targeted to the public and found that the programs “contributed to modest improvement in public knowledge of and attitudes toward depression or suicide,” but could not find that the campaigns actually helped increase care seeking or decrease suicidal behavior. A similar study in 2010 in the journal Crisis actually found that billboard ads had negative effects on adolescents, making them “less likely to endorse help-seeking strategies.”

According to the National Institutes of Mental Health, 90 percent of people who die by suicide in the U.S. suffer debilitating mental illness. Other risk factors include prior suicide attempts, a family history of mental disorders and violence in the home. If we know who’s most at risk, people like Jaffe and Berman argue, shouldn’t we target them in a smarter way? If a factory closes, for example, shouldn’t efforts be made to market suicide prevention services in that community?

SAMHSA is the government’s arm in the field of suicide prevention, and while mental health coverage has been expanded for tens of millions of Americans as part of the Affordable Care Act, SAMHSA’s funding requests for suicide prevention efforts have been decreasing. For fiscal year 2014, SAMHSA requested $50 million for its suicide prevention measures, $8 million less than in 2012. Funding for National Suicide Prevention Lifeline crisis centers to provide follow-up to suicidal callers and evaluate the lifeline’s effectiveness, also decreased by almost $1 million when compared to 2012. SAMSHA did however request a $2 million increase for the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, which, among other things, would be used to develop and test nationwide awareness campaigns.

AAS’s Berman characterizes the national strategy as including both public and targeted approaches to prevention but is concerned that SAMHSA is too focused on “upstream” measures like increasing overall awareness.

“The bottom line is that the people most at risk are people who don’t get into treatment, and a public health approach shifts attention from high-risk patients to large populations of folks who might develop mental health problems,” he says.

However, Richard McKeon, SAMHSA’s acting chief of the Suicide Prevention Branch, says federal efforts have always had a significant focus on people most at-risk. “Much of our suicide portfolio focuses on those who are actively suicidal,” he says. McKeon cites efforts like the collaboration with the National Association of State Mental Health Programs directors, which produced a white paper for state mental health officials so they could better focus on people with serious mental disorders.

McKeon says that focus is evident in the National Strategy, which was revised last year and lays out a comprehensive approach to preventing suicide at the local level. He also cites the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and says it deals not just with people who are depressed, but also with people every day who are at high risk of suicide, 25 percent of which are actively suicidal. But still, the behavioral health of the entire population is a priority for SAMSHA, McKeon says.

“Our suicide prevention efforts do take place within a broad public health context,” he says. “Ideally, we’d like to be able to prevent people from becoming suicidal in the first place.”

A program called the Good Behavior Game, which was awarded $11 million over five years by SAMHSA and is designed to identify early behavioral health problems is one initiative McKeon points to as having an impact on catching people upstream. It’s used in 22 economically disadvantaged school systems across the country and has been cited as effective by the Institute of Medicine. The Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act is used to fund youth suicide prevention programs as well and has been described as successful at raising awareness by peer-reviewed journals like Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior.

“A lot of the work we do is aimed at identifying youth who are at most serious risk right now,” he says. “We are dealing with a lot of high-risk situations among very vulnerable people, but there’s also solid scientific basis for early interventions.”

LifeNet, 11:14 a.m.

It took a little less than an hour for Santiago to get her first call on the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, and it’s in Spanish.

The male caller has contacted the center six times since 7 a.m. He tells Santiago he’s depressed, anxious. He’s hearing things that aren’t there and can’t connect with his psychiatrist. He says he feels like he’s going to die. Actually, he says he already feels dead. This isn’t unusual. This is the kind of thing Santiago and the rest of the operators deal with every day.

Call center operators go through about 100 hours of training before they take their first solo call and are trained to use minimally invasive approaches. EMS is rarely called because it can be very traumatic. Sometimes callers will harm themselves while on the phone, but the operators are trained to know the signs of a real suicide attempt.

“There are people who will cut themselves to try and cope with pain,” says Gloria Jetter, a 29-year-old clinical supervisor. Some will truly attempt to take their own lives while on the phone, but this often shows the deep ambivalence of those who are suicidal. They want their pain to end, but part of them wants to live. That’s the part of them calling people like Jetter.

(MORE: How Cutting Physical Education in Schools Could Hurt Grades)

The caller that stands out for Jetter came about a year ago. A middle-aged male dialed the suicide prevention lifeline incredibly distraught. He felt like he was a burden on his family and thought everyone would be better off if he were dead. “He was drinking heavily,” she says. “And it turned out he was actually driving a truck, and he had called because he was just so horrified at his own thoughts, which was that he had a gun with him in the car and he was going to go shoot himself where someone wouldn’t find out.”

Jetter was able to talk the man into pulling his vehicle to the side of the road. He left the gun in the truck and walked toward a hospital as Jetter stayed on the phone with him for the mile-and-a-half walk. The man was just one of many older men she and her colleagues started hearing from as the recession hit.

A Midlife Crisis

The most stunning statistics to come from the CDC report released in May concern the shockingly high suicide rates for older males. The rates for men aged 50 to 59 increased by almost 50 percent from 1999 to 2010, and LifeNet’s crisis counselors began observing a change in their callers when Wall Street crashed and the Great Recession began to take hold.

While rates went up in cities across the country, it hit rural areas even harder. Wyoming has the highest rates of any state. Park County, home to Yellowstone National Park, had 12 suicides per 30,000 people in 2012. Compare that with the national average, which is closer to 12 suicides per 100,000 people. The woman in charge of coordinating the state’s efforts to prevent suicide is Terresa Humphries-Wadsworth, who has been trying to bring the rate down by targeting those most at-risk.

“In Wyoming, we have a tough-it-out kind of mentality,” she says. “Locally, they call it ‘Cowboy Up’ – being very independent, solving problems for yourself.”

Rural areas have historically had higher suicide rates than urban areas, and most experts believe it’s a combination of several things: higher gun ownership per capita, more isolation from friends, family and suicide prevention resources, and a by-the-boot-straps culture. In the suicide prevention field, Wyoming is a perfect storm.

To start, the state is fourth in gun ownership rates. Keeping guns out of the hands of those with mental illness became a topic in gun control debates across the country after the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., largely focused around the problem of homicide. But gun suicide is actually a bigger problem than gun homicide. According to a report by the Institute of Medicine and the National Research Council, gun suicide accounted for 61 percent of the 335,600 people who died from firearm-related violence between 2000 and 2010.

Besides Alaska, Wyoming also has the lowest population density in the U.S. and only one call center networked to the national lifeline. To counteract the state’s macho culture of self-sufficiency, which often prevents men from seeking help, Wyoming’s mental health officials decided to go looking for them. Last year, the Wyoming Department of Health began reaching out to men who had attempted suicide to better understand why they did what they did and found 10 middle-aged men willing to speak candidly one-on-one.

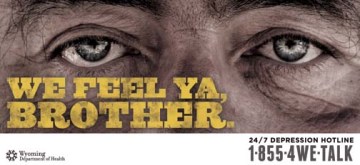

One of several posters created by the Wyoming Department of Health aimed at middle-aged men at risk of suicide. Wyoming has more suicides per capita than any U.S. state.

“When we sat with them, we said, ‘Tell us your story, and go way back,’” says Rich Lindsey, a technical consultant hired to work on Wyoming’s suicide prevention campaign. “We discovered that if you’re going to effectively get to them, you need to go upstream in their life, at a point where things are going wrong but they’re not yet thinking about suicide.”

Lindsey discovered that trying to target a campaign to someone who was already thinking about suicide was more likely to fail because that person was already shutting themselves off from the world around them. The chances of reaching them at that point were slim.

So the state took that information and developed an awareness campaign consisting of local TV ads, billboards and posters featuring an older, rugged man with bushy eyebrows, lonely eyes and phrases like “We feel ya, brother,” “It’s tough out here,” and “Get out of hell,” as well as a unique phone number so they could track the response rate.

The one-county, $50,000 pilot program elicited 10 calls from February to June. Lindsey says it’s too early to says the campaign is a “win,” but it’s been effective enough that the program will be expanded to two more counties. For those who advocate upstream approaches, the Wyoming experiment may be viewed as a model. But for others, $50,000 on a public awareness campaign and a mere handful of calls may not seem worth it.

LifeNet, 11:25 a.m.

Santiago is logging in her previous caller, the man who had called six times that morning. She says he wasn’t actively suicidal and told her that talking to the call center’s crisis counselors helped him make it through the day. But she thought if he called back a seventh time, she would explore getting him to an emergency room.

“What are the chances he’s calling back?” I ask.

“Oh, he’s calling back,” Santiago says. By the end of the day, Santiago will have answered 20 to 25 calls from any one of the 14 different hotlines.

You may think that a suicide prevention office would be a dreadful place to work, but it’s really just like any other around the country: idle chatter near the water cooler, lunch breaks with co-workers, cinnamon rolls in the break room. It’s just that from this room, lives are being profoundly affected every day. And even though the exact number of people who have truly been helped will never be known, the lifeline has very strong advocates, including Kevin Hines.

Hines’ story is not merely dramatic; it’s a test case in how the mental health system broke down. There are essentially three main ways to prevent suicide: treatment; means prevention; and access to prevention resources. At the time, Hines wasn’t properly being treated for bipolar disorder; the Golden Gate Bridge has no physical barriers to prevent suicide attempts; and as for the bridge’s suicide prevention call box, Hines didn’t know it was there.

“Had I known, I’m sure I would’ve called,” he says, “because I desperately wanted to talk to somebody.”

Back in New York City’s suicide prevention call center, I ask Draper if it’s difficult to come in to work each day, to motivate his employees to take another call and assure them that what they’re all doing is actually working.

“When I tell people what I do, they say, ‘Oh, Draper, that must be really depressing,’” he says. “And I say, man, I’m in the suicide prevention business, not the suicide business. What I see every day and what our crisis center staff hears every day is hope. And they know that they’re a part of that.”

He says it’s important to remember that 1.1 million adults are attempting suicide every year, but 38,000 are actually dying by suicide.

“What that is telling us is that by and large, the overwhelming majority of suicides are being prevented,” he says. “And those stories are not being told.”

SEE ALSO: The Big Surprise of Martin Luther King’s Speech

Correction: A previous version of this story stated that in fiscal year 2014 SAMHSA requested $8 million less for suicide prevention measures than in 2013. The department requested $8 million less compared to fiscal year 2012.